Little Nightmares II is a masterclass in silent storytelling, where every sound, object, and flicker of light serves a narrative purpose. Among its most powerful motifs is the television—a seemingly mundane device transformed into a symbol of mental decay, control, and surrender. The television in this game does not simply provide visual flair; it defines the logic of the world, shaping the behavior of its inhabitants and the moral journey of its protagonist, Mono.

This article explores in depth the symbolism of the television and the broader theme of control within Little Nightmares II. We’ll examine how the TV evolves from a tool of curiosity to a weapon of subjugation, and ultimately, a mirror of societal dependence on illusion. Through ten connected sections, we’ll uncover how the developers used this single object to critique both human obsession with media and the fragility of personal will in a world saturated by manipulation.

The Birth of Illusion – Entering a World of Static

When Little Nightmares II begins, the first television lies discarded in the forest. It hums faintly, glowing with eerie static. This introduction immediately links the medium to both decay and fascination—it calls to Mono even before he understands its purpose.

The television’s presence in a natural, untouched environment signals its corruption of innocence. It doesn’t belong in the forest; it’s an invader. Yet Mono’s curiosity toward it feels instinctive, revealing the game’s central paradox: humans are irresistibly drawn to their own means of control.

The First Signal of Manipulation

The static becomes the game’s language for conditioning. Its soft, rhythmic pulse mimics hypnosis. Even before the player realizes the TV’s power, it has already begun shaping behavior—just as media does in real life.

The City of Screens – Civilization’s Addiction

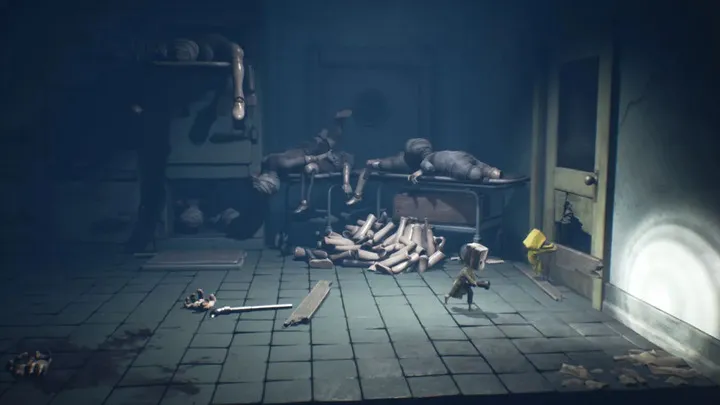

Upon entering the Pale City, the role of the television transforms from curiosity to necessity. The citizens—faceless, hollow figures—stand frozen before their screens, consumed by flickering light. Their bodies remain still, their minds lost in transmission.

This visual metaphor captures the death of individuality. The people of the Pale City are not victims of monsters but of surrender. Their endless staring represents the abandonment of thought in exchange for distraction. The game’s quiet horror lies in how normal it feels—how easily the player recognizes the scene as familiar.

The Architecture of Control

The entire city is built around televisions. Cables snake through walls, rooftops, and apartments, binding the environment like veins. The infrastructure of the Pale City becomes a literal network of dependency, showing how control operates not through force but through comfort.

Mono and the Static – The Gift and the Curse

Mono’s ability to interact with televisions distinguishes him from everyone else. Unlike the entranced citizens, he can step into the static, bend it, and emerge on the other side. This skill is both empowering and damning.

The game presents this power ambiguously. On one hand, Mono uses TVs to escape danger and navigate the city; on the other, each use brings him closer to corruption. The static begins to pulse in rhythm with his heartbeat, suggesting a deeper connection between him and the Broadcast Tower.

Power Through Submission

Mono’s control over televisions mirrors humanity’s paradoxical relationship with technology: the more control we believe we have, the more dependent we become. His mastery is an illusion—the TVs respond to him only because he is already attuned to their frequency.

The Broadcast Tower – The Source of Corruption

At the heart of the Pale City stands the Broadcast Tower, the origin of all signals. Its twisted architecture rises above the fog like a physical manifestation of control. The tower doesn’t just transmit static—it emits obedience.

Every citizen, every screen, and even Mono himself are linked to this monolithic structure. The tower represents the ultimate consolidation of influence. It has no voice, no face, and no motive—it simply is, reflecting the faceless authority of modern media.

The Ethics of Invisible Power

The tower’s silence is intentional. Its control lies in its invisibility; by never speaking, it removes the need for justification. In this world, domination becomes ambient—omnipresent yet unnoticed.

The Thin Man – Embodiment of the Signal

The Thin Man, the game’s most haunting figure, is the Broadcast Tower’s living emissary. His body stretches unnaturally, as if pulled by the static itself. Every step he takes distorts reality, and televisions become his gateways.

He represents what happens when control ceases to be external and becomes intrinsic. The Thin Man no longer needs the television—he is the broadcast. The static flows through him, suggesting that he was once human but was consumed by the same power Mono flirts with.

The Face of Surrender

The Thin Man’s lack of emotion mirrors the citizens’ numbness. His movements are slow, deliberate, and drained of humanity, embodying the final stage of surrender—when individuality is overwritten by frequency.

Six and the Static – The Witness to Corruption

While Mono interacts directly with televisions, Six remains an observer. She sees what they do to others but cannot understand their lure. Her reactions—hesitation, fear, disgust—offer the player an external moral lens.

As the story progresses, however, Six’s detachment fades. Exposure to the static, and to Mono’s growing obsession, subtly alters her behavior. By the final act, her choices mirror the same apathy she once feared.

The Contagion of Influence

Control in Little Nightmares II spreads like a virus. Six doesn’t need to touch the television to be infected; proximity is enough. The signal is emotional—it travels through fear, trust, and betrayal.

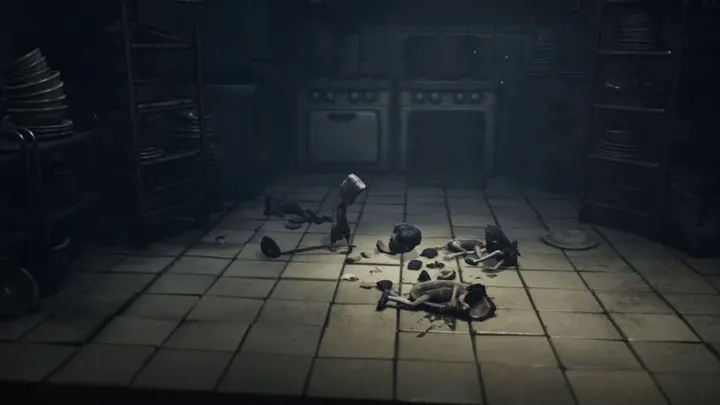

The Collapse of the Tower – Illusion Shattered

When Mono and Six ascend the Broadcast Tower, the visual language shifts from realism to surrealism. Walls melt, corridors twist, and the static becomes a living organism. The tower’s interior exposes what control looks like from within: chaos masquerading as order.

The destruction of the tower doesn’t signify freedom but revelation. The illusion collapses, revealing that Mono’s connection to the static was never accidental. The tower was grooming him, preparing him to replace the Thin Man.

Liberation as Deception

Even when the player believes they are dismantling the system, the system adapts. Little Nightmares II uses this moment to emphasize that rebellion within a framework of control often becomes another form of control.

The Final Betrayal – Breaking the Signal Chain

The moment Six drops Mono’s hand is the game’s emotional core. Her decision severs the link between them—and symbolically, between humanity and dependence. Yet it’s a tragic act, not a triumphant one.

Six’s release mirrors society’s occasional rejection of manipulation—momentary and incomplete. By letting go, she escapes, but Mono becomes what she refused to be. The chain is broken but replaced by another.

Betrayal as Consequence, Not Choice

Six’s betrayal is inevitable. Her actions are shaped by exposure, not autonomy. The game suggests that once corrupted by influence, free will itself becomes suspect.

Mono’s Transformation – Becoming the Broadcast

Mono’s final metamorphosis into the Thin Man completes the symbolic cycle. The child who once fought against the signal becomes its transmitter. This transformation is the perfect tragic loop—a commentary on how systems of control regenerate through those who resist them.

As Mono sits in the chair, surrounded by pulsating static, the world forgets his face. His individuality dissolves into signal, and the Tower reawakens. Control persists not because it is invincible, but because it learns to wear new faces.

The Machinery of Continuity

The ending demonstrates how power is never destroyed—only redistributed. Every rebellion feeds the next generation of control, ensuring the static continues to hum forever.

The Player’s Reflection – Our Place in the Broadcast

Little Nightmares II does not accuse; it implicates. By forcing players to use televisions as lifelines, it turns them into participants of the same system they are meant to escape. The satisfaction of solving a TV puzzle mirrors the pleasure of consumption—it rewards engagement with control.

The player becomes the missing link in the cycle. Each activation of a screen reinforces the theme that dependence on mediated reality feels safe, even when it enslaves. The horror, ultimately, is not what happens in the game—but what it reveals about us.

Beyond the Screen

When the credits roll, the player’s own screen becomes the final television. The static fades, but its echo lingers, reminding us that the broadcast never truly ends—it merely changes channels.

Conclusion

Little Nightmares II uses the television as a profound symbol of manipulation and surrender. Through Mono’s descent, the player witnesses how technology and control intertwine to reshape human will. Each screen, each pulse of static, becomes a metaphor for the fragile boundaries between autonomy and obedience.

The game’s brilliance lies in its refusal to moralize. It doesn’t tell us to turn off the screen—it asks whether we could, even if we wanted to. In a world defined by constant transmission, Little Nightmares II doesn’t just show horror—it broadcasts it directly into our reflection.